What facilitates the implementation of PBL, and how can we evaluate the progress our students have made? “Modern digital technology, group processes of high quality, teachers’ ability to effectively scaffold students’ learning and provide guidance and support, the balance between didactic instruction with in-depth inquiry methods and well-aligned assessment have been identified in the literature as facilitating factors in the implementation of PBL” (Kokotsaki, Menzies, & Wiggins, 2016).

We’ve already covered almost all of the above features of Project-Based Learning (PBL) in our previous two installments: launching and monitoring PBL. It is now time to break down the last stage of this process: evaluating projects and assessing students.

While project evaluation can be an interesting – even pleasant – process for educators, student assessment can be quite tricky. Many of us are concerned with the fact that PBL is a profoundly inquiry-based educational approach and it doesn’t seem to be a good fit with traditional assessment methods. How do we respond to this challenge by assessing innovatively?

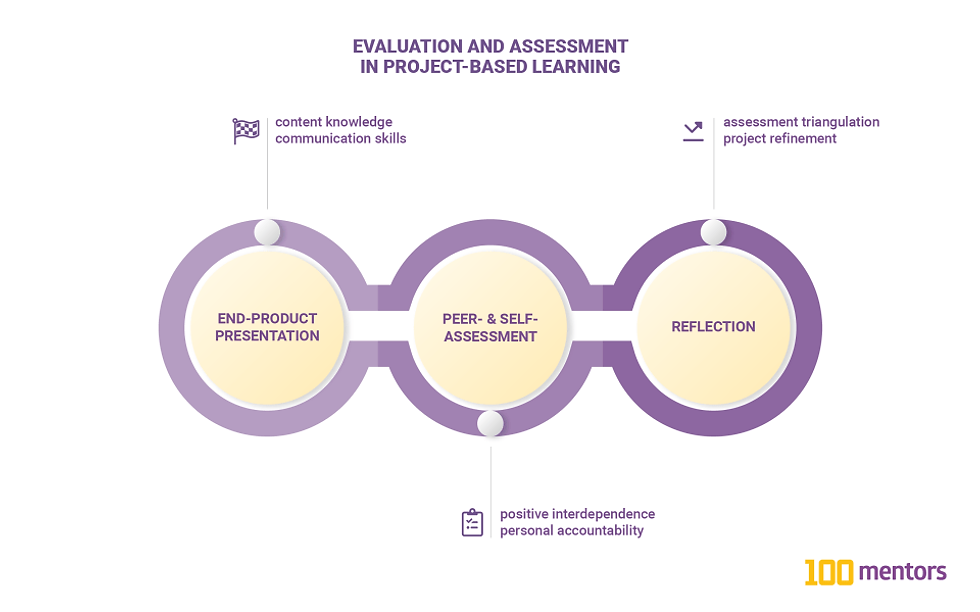

In PBL, we have our students solving real-life problems and we intend to empower their 21st-century skills; in other words, we establish meaningful connections between school and life beyond school. It goes without saying that we should assess both students and these outcomes in an equally “authentic” way (Bell, 2010). This includes the presentation of the end-product to an appropriate audience, peer- and self-evaluation through rubrics, and opportunities for reflection.

Stage 3: Evaluating PBL

1. End-product presentation

This is the moment we have all been waiting for: our students are about to present the ultimate outcome of their project-based work. They may feel intimidated by this prospect, but they also may feel proud of their accomplishment. More often than not, they’re right to be so.

Our students will be juggling with many aspects during their presentations: alongside content knowledge, they will have to demonstrate their research, thinking, communication, and self-management skills, too. Therefore, when evaluating students’ end-products, standardized tests are not the way to go. It would be better if we used a tailor-made rubric to cover the whole range of content and skills that should have been nurtured through these particular projects. This doesn’t have to be as much work as it sounds.

2. Peer- and self-assessment

Although a teacher-controlled assessment is an objective metric for students’ performance, this “authentic” learning environment calls for a variety of assessment methods. Especially if students have been working in groups, teammates should evaluate each member’s positive interdependence, and every one of them should be given the chance to estimate their level of personal accountability. To create a common ground for peer- and self-assessment, we can design a rubric in collaboration with our students.

Students don’t assess each other’s knowledge construction; they assess certain skills from the perspective of a “critical friend.” Therefore, their peer-assessment rubric should examine “how well they contributed, negotiated, listened, and welcomed other group members’ ideas” (Bell, 2010). Let them know that their goal is to provide constructive feedback that would emphasize their teammates’ strengths, and mention where there is still room for improvement.

It will be interesting for you to see how well teacher- and peer-assessment fit with each student’s self-assessment. Students evaluate their personal contribution to the project in terms of effort, motivation, and productivity. They should also take a critical look at their social interactions and communication endeavors. At the end of the day, they should estimate to what extent these factors affected their learning.

3. Reflection

The PBL process seems to be complete at this point – but it’s not just yet. Each student has just been given a three-fold assessment, and now we should ask them to make sense of it. They should be given some time to triangulate these reports and realize what went well and what went wrong. To ensure their “active reflection,” you may even allow your students to make some final refinements to their projects.

I guess that many educators now reading this are deliberating about how great all these assessment methods sound… but what about the mandatory formative assessment tasks? Will our PBL students perform well when the time comes?

Well, there’s good news! Several studies across subjects indicate that students engaged with PBL outperform their peers that participated in traditional instructional settings (Bell, 2010). This refers to both standardized assessments and project tests. And beyond knowledge construction, our PBL students have cultivated a few crucial 21st-century skills along the way – teamwork, communication, and self-management.

Now we have all the necessary components to successfully implement PBL with our students. Keep in mind that this strategy requires efficient EdTech scaffolding and resourceful linking to a global community. With 100mentors, you can do both, inside or outside the classroom.

Sources

Bell, S. (2010). Project-Based Learning for the 21st Century: Skills for the Future. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 83(2), 39–43.

Kokotsaki, D., Menzies, V., & Wiggins, A. (2016). Project-based learning: A review of the literature. Improving Schools, 19(3), 267–277.

Comments